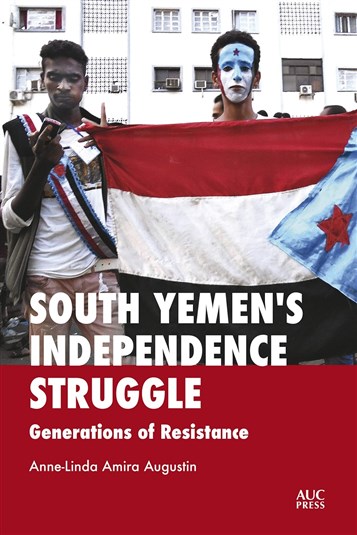

Anne-Linda Amira Augustin, South Yemen’s Independence Struggle: Generations of Resistance (Cairo/New York: The American University in Cairo Press, 2021).

Jadaliyya (J): What made you write this book?

Anne-Linda Amira Augustin (AAA): In 2007, the Southern Movement was born in protest against the marginalization of South Yemenis since the unification of the People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen (PDRY/South Yemen) with the Yemen Arab Republic (North Yemen) in 1990. In this same year, I spent a semester at the University of Aden within the scope of my Middle Eastern studies at Leipzig University in Germany. At that time, most students of Middle Eastern studies traveled to and studied in Egypt or Syria. However, descending from an East German mother and a South Yemeni father, my personal background was the source of my interest in this region, which normally gets little attention in Middle Eastern studies. Ever since the Movement’s emergence in 2007, I have wanted to learn and understand more about it.

I often wondered about the very active involvement of young South Yemenis in the Southern Movement and these young people’s accounts of how great life was in the PDRY. I was born in the German Democratic Republic (GDR) in the mid-1980s. I was a young child when the two Germanys reunified, so I have few memories of life in the GDR before then. I was astonished when young South Yemenis born after 1990 told me “we had” these and those accomplishments in the PDRY, and “our state” provided “us” with these and those achievements. I wondered why they so strongly identified with a state that disappeared from the world map more than two decades ago. Thus, I began questioning why so many young people had joined the Southern Movement, why they demanded the reestablishment of a state they had never experienced, and where their conception of the PDRY had originated.

J: What particular topics, issues, and literatures does the book address?

AAA: The book is the first ethnography of the South Yemeni independence struggle, working from a grassroots perspective with historical aspects of the PDRY era, the time after Yemeni unification in 1990, and the formation and consolidation of the Southern Movement. It is built from a rich empirical basis of interviews, focus group discussions, textbooks, social media, print media, poems, song texts, photographs, testimonies of conversations with activists, neighbors, and so on, and thick descriptions of situations I observed in recent years.

I argue in this study that the desire for independence was present long before the Southern Movement emerged in 2007 but then was far from public attention: it was within families, neighborhoods, and circles of friends and colleagues that memories of the past and the demand for reestablishing the state on the territory of the former PDRY were maintained—from the period of unification, but particularly after the 1994 war until 2007. Around these memories, resistance was organized and claims for the reestablishment of the independent state were circulated privately until they could be expressed publicly with the emergence of the Movement.

The generational dimension of the independence struggle is core to this form of resistance and its continued existence. I show that, in a resistant environment, intergenerational transmission is not the monopoly of the family only, but that neighbors, friends, activists of a movement, journalists, media-makers, and academics play an important role in an independence struggle to transmit counter-memories and the wish to regain a lost state. Thus, the book opens up new vistas on everyday forms of resistance from below within a very repressive environment, which are far from overt forms of resistance against regime violence and suppression, such as protests and strikes.

J: How does this book connect to and/or depart from your previous work?

AAA: Since I finished my Masters in Middle Eastern studies in 2011, I have been focusing my research on the Southern Movement and the independence struggle in South Yemen. Thus, the book is the result of more than a decade of research in and on this region and the Movement. The book is based on my PhD thesis which I concluded in 2018 at Marburg University in Germany.

J: Who do you hope will read this book, and what sort of impact would you like it to have?

AAA: South Yemen, like Aden and surrounding governorates, is an under-researched region in Middle Eastern studies; thus, publications on South Yemen are rare, as are publications on Yemen in general. The research for this book was conducted under very difficult conditions on the verge of war in 2014 and 2015. Already at that time, access to South Yemen has been restricted due to the security situation in the country. As the war in Yemen continues and an end of the war is not yet foreseeable, for the upcoming years the book might remain the last ethnographic research conducted in the country and on this persistent Arab uprising.

Besides a broader audience interested in the Middle East (especially in Yemen), the book is intended to attract an audience of anthropologists and social and political scientists with a focus on resistance, independence struggles, memory studies, narratives, spaces, actors and activists, protest movements, and intergenerational relations.

Furthermore, the book has a global appeal, because it provides insight into why Yemen is at war today. The grievances in South Yemen and the claims for independence are one of the very or even the most urgent political issues in Yemen, challenging the territorial integrity of the Republic of Yemen. South Yemenis have been able to keep alive their aspirations for regaining their state on the territory of the former PDRY after more than three decades of unification and repression from the central government. Thus, the book is very topical at this time, especially as the United Nations tries to bring together Yemeni parties into peace talks to solve the war, and it will be very relevant for the coming years, as it helps us to understand the major political challenges the Republic of Yemen faces today and will face in the future.

J: What other projects are you working on now?

AAA: Due to the war in Yemen, it is impossible to do extended field research in Yemen. I am currently working as a research coordinator at Leipzig University in Germany, coordinating a joint research project on institutions and racism in Germany, funded by the German Federal Ministry of the Interior.

J: What do you mean by “intergenerational resistance”?

AAA: In the book, I argue that intergenerational transmission becomes a “weapon of the weak” (James Scott, 1995, xvi), an everyday form of resistance of relatively powerless people, which requires little to no coordination or planning. Such forms of resistance can be very efficient in the long run because they avoid full and direct confrontations with authorities.

Intergenerational transmission as an everyday form of resistance, what I term intergenerational resistance, can proceed for many years before its effects appear publicly and turn into political mobilization. The delayed outcomes of intergenerational resistance explain why the Southern Movement did not emerge immediately after the war in 1994, but rather in 2007, the time when those born after unification came of age and joined the resistance.

Excerpt from the book (from the Introduction, pp. 1-3)

In 2007, I spent several months in Aden, South Yemen, completing a semester at the University of Aden within the scope of my Middle Eastern Studies at Leipzig University in Germany. In that same year, the Southern Movement (al-Hirak al-Janubi, hereafter, the Movement) was born in protest against the marginalization of South Yemenis since the unification of the People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen (PDRY; also known as South Yemen; Jumhuriyat al-Yaman al-Dimuqratiya al-Sha‘biya) with the Yemen Arab Republic (YAR; also known as North Yemen; al-Jumhuriya al-‘Arabiya al-Yamaniya) in 1990; that marginalization increased after the war in 1994.

At the time of Yemeni unification in 1990, power in the state was equally shared between South and North Yemeni politicians and bureaucrats in ministries. However, the results of the 1993 elections shattered the power-sharing agreement, marginalized the Yemeni Socialist Party (YSP; al-Hizb al-Ishtiraki al-Yamani) of the PDRY, and strengthened the General People’s Congress (GPC; al-Mu’tamar al-Sha‘bi al-‘Amm) and the Yemeni Congregation for Reform (Islah Party; al-Tajammu‘ al-Yamani li-l-Islah) and, with them, the tribal and Islamist elites of North Yemen. Due to fundamental disagreements in the new coalition government that the three parties formed, tensions soared and war broke out, beginning with clashes on April 27, 1994. On May 21, 1994, the PDRY faction proclaimed the establishment of the Democratic Republic of Yemen within the territory of the former PDRY; however, it lost the war on July 7, 1994, and the Republic of Yemen remained one entity.

When it began, the Southern Movement was a loose merger of South Yemenis, many of them former army personnel and state employees of the PDRY who had been forced from their jobs after the war in 1994. For those affected, the elimination of their jobs was tantamount to punishment for the war. In 2007, these people began to express their discontent publicly, demanding social rights and pensions or to be reinstated in their jobs. However, the Yemeni government would not address their grievances. State security forces used brutal measures against protesters (see Human Rights Watch 2009), which had the effect of strengthening the heretofore weakly organized social movement. More and more people joined the demonstrations, and the grievances evolved into concrete political demands, foremost among which was the demand for state independence of the territory that once formed the PDRY.

By 2007, when I was studying in Aden, everybody there seemed to be talking about the emergence of the Southern Movement; ever since, I have wanted to learn more about it. I often wondered about the very active involvement of young South Yemenis in the Southern Movement and these young people’s accounts of how great life was in the PDRY. I was born in the German Democratic Republic (GDR) to an East German mother and a South Yemeni father, so my own background is situated in two states that both disappeared from the world map through unification processes with their neighbors in 1990. I was a young child when the two Germanys reunified, so I have few memories of life in the GDR before then. I was astonished when young South Yemenis born after 1990 told me “we had” these and those accomplishments in the PDRY, and “our state” provided “us” with this and that achievement. They strongly identified with a state that had disappeared before they were born. I began questioning why so many young people born after 1990 had joined the Southern Movement, why they demanded the reestablishment of a state they had never experienced, and where their conception of the PDRY had originated. My own background, which was deeply affected by the topic itself, provided me with some preliminary answers.

In many East German families, nostalgic notions of the defunct socialist state were shared with and disseminated to younger generations. My generation—those who experienced the difficulties of the early unification years during their childhoods—grew up with this “Ostalgia.” This nostalgia taught me that the GDR was a place where people led satisfying lives, cultivated permanent and steady friendships with neighbors and colleagues at work, had lovely parties with their collective work teams from factories, went on fun excursions, and lived a life in solidarity with each other. Some people still seem to miss these things today. Furthermore, jobs then were safe. Job security was scarce in eastern Germany in the 1990s and was certainly a very important trigger for nostalgic notions of the GDR era.

I often heard similar accounts in South Yemen. During my stays in the village in Abyan, I would accompany my grandmother while she tended her goats and sheep every morning, and she would tell me about the past under British colonial rule and about life in the PDRY. Other relatives, friends, and neighbors likewise filled my imagination with pictures of a splendid time before 1990. However, nostalgia for the socialist past could not adequately explain why a mass protest movement with demands for state reestablishment emerged in South Yemen, when similar ambitions had not emerged in today’s eastern Germany. This raised another important question, closely related to the first one, on youth participation: Why had the Southern Movement grown so tremendously during the past decade, developing from a primarily social movement demanding socioeconomic rights into a mass protest movement claiming independence for a state that had long ago disappeared from the world map? I found an answer to my questions by exploring in depth, over a decade, the Southern Movement itself and the principal characteristics of the independence struggle in South Yemen.